|

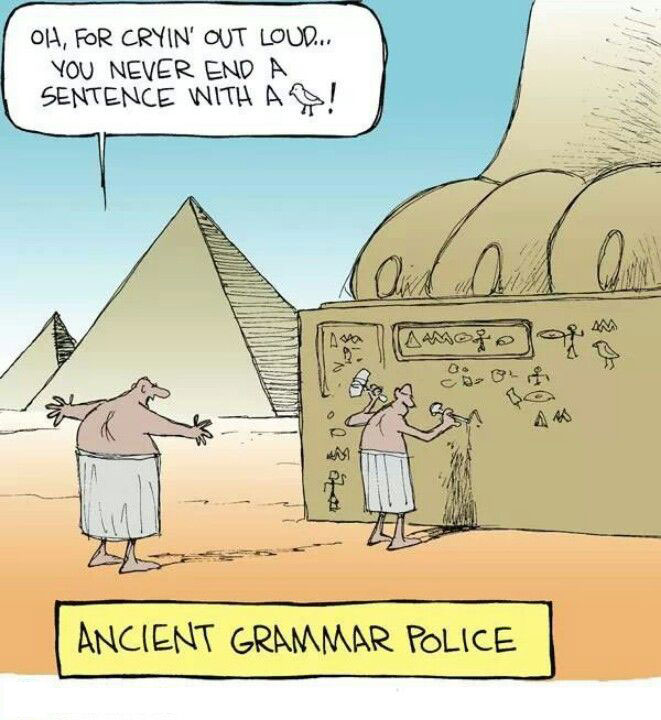

We’ve written a newsletter article about it (Problems with Prepositions), and in Rule 1 of Prepositions we state, “One of the undying myths of English grammar is that you may not end a sentence with a preposition.” Yet, we still receive admonitions from well-meaning readers who think we've made an error when ending a sentence with a preposition. Where did this myth originate, and how did it become such a prevalent belief?

Thanks to loyal reader Yvonne V. for alerting us to an excellent article

that should put this myth to rest—for all who read it anyway.

Where the “No Ending a Sentence With a Preposition” Rule Comes From

It all goes back to 17th-century England and a fusspot named John Dryden.

by Dan Nosowitz

There are thousands of individual rules for proper grammatical use of any

given language; mostly, these are created, and then taught, in order to

maximize understanding and minimize confusion. But the English language

prohibition against “preposition stranding”—ending a

sentence with a preposition like with, at, or of—is not like this. It

is a fantastically stupid rule that when followed often has the effect of

mangling a sentence. And yet for hundreds of years, schoolchildren have

been taught to create disastrously awkward sentences like “With whom

did you go?”

The origins of this rule date back to one guy you may have heard of. Of

whom you may have heard. Whatever. His name was John Dryden.

Born in 1631, John Dryden was the most important figure throughout the

entire Restoration period of the late 17th century. He was more prolific,

more popular, more successful, and more ambitious than any of the other

writers of his era, and his era included John Milton. He was

England’s first official poet laureate. He wrote dozens of plays,

poems, works of satire, literary prose, and criticism. The best modern

edition of the collected works of John Dryden took the University of

California Press about 50 years to create, and runs to 20 gigantic volumes.

He perfected the heroic couplet, making it a standard part of English

poetry. He was the most important translator of classics into English for

hundreds of years, possibly ever. He was, without a doubt, the guy

in the London literary scene of the late 17th century, and that was a very

important scene.

That said, Dryden was roundly mocked by his contemporaries. He does not

seem to have been particularly well-liked. “There is more hostile

response to Dryden than there is to any other early modern writer—I

think than any other writer, period,” says Steven Zwicker, a

professor at Washington University in St. Louis who is one of the premier

Dryden scholars in the world.

Dryden twice stated an opposition to preposition stranding. In an afterword

for one of his own plays, he criticized Ben Jonson for doing this, saying:

“The preposition in the end of the sentence; a common fault with him,

and which I have but lately observed in my own writing.” Later, in a

letter to a young writer who had asked for advice, he wrote: “In the

correctness of the English I remember I hinted somewhat of concludding

[sic] your sentences with prepositions or conjunctions sometimes, which is

not elegant, as in your first sentence.”

Dryden does not state why he finds this to be “not elegant.”

And yet somehow this completely unexplained, tiny criticism, buried in his

mountain of works, lodged itself in the grammarian mind, and continued to

be taught for hundreds of years later. This casual little comment would

arguably be Dryden’s most enduring creation. It’s a little bit

sad.

Following the death of Oliver Cromwell, England was in a pretty weird

place, and the English language was in a weirder one. The monarchy had been

restored, but during Cromwell’s reign an awful lot of English writing

had been stunted; for a time, plays were even banned, for fear of public

political criticism. That’s a bigger deal than it sounds, because

during the latter half of the 17th century, literacy rates in

London—by far the highest in the country—were only around 20

percent. The language evolved on the stage, and that development was paused

for a few decades.

At the time, there were at most a handful of what are called English

grammars: basically, books instructing the proper way to use the English

language. In the Restoration period, when Dryden was a star, the discussion

of exactly what the English language was (and, in turn, who the English

people were, and what England was) began to really rapidly evolve. Dryden

is not very well-known today, but at the time he was the leading literary

rockstar, and his words carried a huge amount of weight. He wasn’t

really one of the leading grammarians of his time, being focused more on

his plays and criticism, but he did, says Zwicker, have very firm opinions

about what he considered good writing and what he considered bad writing.

Other writers of the time were hostile to Dryden, attacking him for

changing his religion from the Church of England to Roman Catholicism, his

political affiliation, for his ambition, and, it seems, because he was sort

of a boring and witless conversationalist. You might expect that the guy to

ban preposition stranding would be a pithy Mark Twain or Oscar Wilde type,

full of great barbed quotes. But Dryden wasn’t that at all. “No

one admired him for his verbal wit,” says Zwicker. “Certainly

his writing is wonderful and clever, but he had practically no verbal

presence at all.”

It is actually a bit of a mystery why he was so loathed at the time;

Zwicker suggests some of it was probably envy at Dryden’s success,

some was legitimate criticism of his style, and some was vague personality

stuff. But a lot of this stuff seems like subtext, as if Dryden was

attacked because he was Dryden and the reasons given might not have been

telling the full story.

Dryden loved the classics; he was easily the most prominent translator and

critic of Ovid, Horace, and Virgil, although his translations (like a lot

of his own writing) were sort of bombastic and larger-than-life. He was

fluent in Latin and worshipped the classics. And English was in a place

where it was about to accelerate; it had been paused and now it was

un-paused. Dryden’s ideas about what English should be were heavily

motivated by Latin and Latinate ideas. It’s believed this is where

his preposition thing comes from; in Latin, the preposition, as indicated

by the first three letters of the word “preposition,” always

comes before the noun. It is assumed that this is what motivated Dryden to

make this case.

This is kind of a paradox as well; Dryden worshipped the classics, and was

motivated by classical Latin, but was a defiant modernist, maybe even a

progressive. He critiqued Shakespeare and Ben Jonson, applauded the newer

writers of his own era, invented new forms which he then sought to

popularize. But that’s the hold that the classics have: even when

you’re trying to push things forward, the classics are always there.

What’s so frustrating about this whole preposition thing is that

there doesn’t appear to be an easy answer as to how it became so

completely lodged in formal English grammar. There are all these little

hints as to why it might have taken hold—it is an easy-to-understand

grammarian rule that came about at a time and place when English grammar

was rapidly taking form, and it came from the mouth of the biggest literary

figure of the time. But like Dryden himself, it’s a hard rule to get

ahold of. Of which to get ahold.

|