|

Few will ever forget the words spoken by Winston Churchill in June 1940

under the thickening shadow of Nazi aggression:

“We shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight

in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with

growing confidence and strength in the air, we shall defend our island,

whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on

the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we

shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.”

In a moment of such immortal conviction, none would have thought to

question whether Churchill was using the correct auxiliary verb to express

his nation’s resolve. His words are as powerful and inspiring today

as they were almost 80 years ago.

Notwithstanding, if English teachers of the day had reviewed

Churchill’s speech before he gave it, they would have alerted the

leader to the usage of shall versus will:

• To express a belief regarding a future action or state, use shall. To express determination or promise (as Churchill was), use will. As a further example, a man who slips from a roof with no one around and hangs on to it by his fingers will cry, “I shall fall!” A man who climbs to a roof in order to fall from it will cry, “I will fall!”

• To simply communicate the future tense (without emphasis on determination, promise, or belief) in formal writing, use shall for the first person (I, we) and will for the second and third persons (you, he, she, they):

I shall go to the store tomorrow. They will go to the store tomorrow.

Such established grammatical strictures once made discerning shall from will easy for English users. Through the

years, however, the words’ functions have blurred; in common writing

and speech, they are often interchangeable and seldom precise.

Adding to the matter, style and grammar sources offer differing views on

when to use shall or will. The Harbrace College Handbook asserts the auxiliaries are transposable

for the first, second, and third person. It also declares will is more common than shall; shall is used

mainly in questions (Shall we eat?) and might also be used in

emphatic statements (We shall overcome.).

It further upholds the teaching of Churchill’s day to use shall in the first person and will in the second and

third to express the simple future tense or an expectation: I shall stay to eat. He will stay to chat with us.

To communicate determination or promise, however, it slightly departs from the Queen's classic English. Rather than always use will, it flips its order for the future tense or an expectation (i.e., will in the first person; shall in the second and third). Grammatical form for those intent on falling from a roof would thus be "I will fall!" (first person) or "You shall fall!" (second person).

Perhaps more pliable and contemporary, The Rinehart Guide to Grammar and Usage suggests the words’

loose and inconsistent usages have rendered them identical. This other

book’s only discernible guideline is that shall is the more

stuffy of the two auxiliaries; it seldom appears anymore except in a

question or with the first-person I or we.

Moving in yet another direction, The Associated Press Stylebook directs us to use shall to express determination in all

circumstances (I shall win the election. You shall win the election. She shall win the election.). It also points out that either will or shall may be

used in the first person when not emphasizing determination: I shall stay to eat. I will stay to chat with them. For the second

and third persons, use will unless emphasizing determination: He will stay to eat but They shall win the election.

The Chicago Manual of Style

puts forth that will is the auxiliary verb for the future

tense, which conveys an expected action, state, or condition (Either he or I will stay to eat). It further suggests that will is now more common and preferred than shall in

most contexts. In American English, it says, shall can replace will, but the most typical usage will be in first-person

questions (Shall we stay to eat?) and in statements of legal

requirement (You shall appear in court three weeks from today.) It further specifies that must is a better word than shall for statements of legal requirement.

In his seminal book The Careful Writer, Theodore M. Bernstein says

the heck with it all:

A speech such as Churchill’s proves we can override any

grammatical doctrine for shall or will.

He notes that if anything, will appears to be the favored

auxiliary in most declarative sentences and shall is used for a

touch of formality. In other words, no matter when or where you use shall or will, you’re probably right.

We agree—but you don’t have to. If you prefer strict and clear

guidelines, they exist: Simply choose your stylebook. If on the other hand

you believe shall and will should be free to stand in for

each other, you already have such privilege to swap.

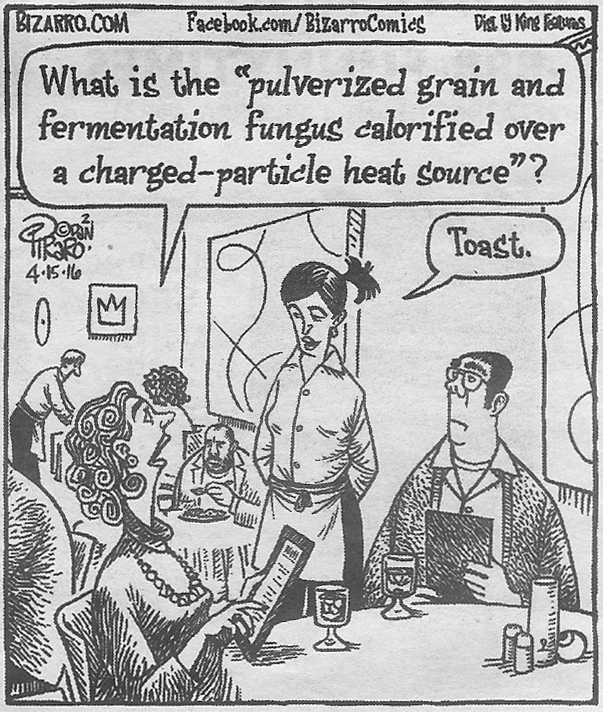

So let’s write as we will, shall we?

|